- Home

- Holloway, Daniel;

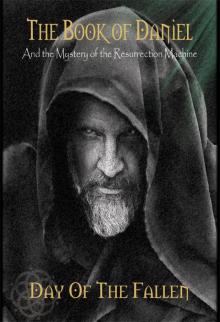

The Book of Daniel and the Mystery of the Resurrection Machine Page 2

The Book of Daniel and the Mystery of the Resurrection Machine Read online

Page 2

Yet the serpent of my dreams was, somehow, the most wonderful creature I’d ever seen. It was my friend and I knew it. He was large, as big as a python, and deadly poisonous. Each night in my visions I walked to a distant mountain where I knew this viper awaited. There he would coil and raise. Staring with his golden-yellow eyes, he peered into my soul, mouth open, fangs agape, dripping their deadly elixir.

Surprisingly, however, I was always glad to see him, my soul at ease within his presence. Each time I placed my finger between his fangs, upon them scribed the word; “vengeance”. Gently I touched the tongue of the serpent’s mouth; it too had a word written across its length, the word; “truth.” Each time my skin absorbed the fruits of this touch, my finger pricked with the tip of vengeance, then healed with the word of truth that followed; one countered the other.

As this happened, I could read the creature’s every thought. I knew his mind and he knew mine. Glowing with a beautiful luminescence, he too was mesmerized in the moment, suspended in marvel with what he saw in my eyes—a reflection, somehow, of himself. Without words he told me that something great was about to happen and that he would soon return to the world. It was then that I would turn and leave.

Even in this dream I was elated with the joy of his promise but also with a sadness that I had to go. Unfazed by the venom, I awoke each time in a restful bliss. Yet between this dream and the image of moonlight that first morning, I was unsure if these somehow had meaning or if they were only the result of having inhaled too much ammonia. Had not the dreams precluded my field work, I would have surely suspected the latter.

Ah but the dreams of a dreamer. One must carry on with the task of making money. A farm the size of ours provided only a supplemental income and required me to work a full-time job as well, as a tire tech at a concrete plant in Louisville. But between that and the farm, I did well enough and wanted for little.

No doubt I was a bit rough around the edges. Blue jeans, boots and a tattered shirt were my daily wardrobe. My hat was my comb. If I forgot my belt, then bailing twine always sufficed. Often, fishing line and a needle were my stitches, and duct tape for the rip in my britches. I was down to earth and truly geared for the life of a farmer, but I was happy and free as a bird.

It was a different day then, a different time. Work rather than relaxation was the norm and I stayed busy. Yet it was still easier to avoid the rat race then than it is today. I loved my life: working the fields, the tobacco, the hay, the hogs, the corn, and the cattle. I even enjoyed changing truck tires. I was in fantastic physical condition, though a bit naïve to the ways of the world. No doubt I was wild as a buck and wired tight—an average, everyday country boy.

I had my tortures, however. Weddings, church, and funerals were always unwelcome endeavors. The real problem was the discomfort of dressing up—the choke of the tie and the itch of a woolen coat. The pretense of show always made me feel out of place, and I could never seem to grasp how others enjoyed such occasions. The whole town knew I was a bit wild; but if so, why then did I have to pretend to be something else as were they?

Yet I’d always attend these gatherings out of respect. With a deep breath, I’d stand up straight and simply play the role. In the end I suppose respect is what it’s all about and that was good enough for me. That said, I could never reach the farm fast enough and slide back into the comfort of my well-worn duds.

Aside from that, life was my hobby. I enjoyed my diversions: hewing logs, running the woods, hunting—all of which kept me pleasantly occupied. I was honest to a fault, with a genuine love for the truth, whatever it may be, and lived my life accordingly.

I thought about God as well. As with many folks, I contemplated spiritual things: the meaning of life, the origin of the universe, and my place therein. How did it all fit? How did it all happen, and why? I wanted to know. I wanted it to make sense. I wanted real answers.

In context, church I suppose was as much a social-function as anything. Plus, in a small country town it was the only media by which to track your neighbor. There were three churches: the Methodist, the Baptist and the Christian, all within a block. And by no surprise we rotated freely between them. Their doctrinal differences weren’t that great (they all used the same Bible), so to alternate from Sunday to Sunday was common for all except the most die-hard Baptists. Plus, it kept us close; it preserved the bond of community, as well as the web of support in times of need.

Being from the Bible belt of course we presumed the answers to our spiritual inquiries were hiding somewhere within the pages of that ancient text. It was the umbrella under which we’d been raised, the rolodex for our religious questions. Basically, the Bible says “this,” therefore it’s the “answer”—now “deal with it”!

Yet there were times it didn’t satisfy my craving for truth. Something was missing. Either I didn’t like the answers or sometimes my questions were simply too big. I wanted more details than what my preachers could give. The problem was that my ponderings were often socially unacceptable and, according to those who deem themselves devout, even blasphemous.

They insisted that the power of the universe has already given us the instructions by which to play the game of life. They condemn with great swelling words of authority too. Yet I couldn’t tell if it was heads or tails; was it authority they possessed or arrogance? Due to the fact that most folks don’t really know the scriptures, we typically have little with which to refute those who are morally confident.

Many wish to believe yet have limited options on what to believe. Often, free thinking has little place in the world’s structured belief systems, thus we only question just so far. We settle back into the status quo of saying, believing, and doing things according to the direction of those in charge of our spiritual beliefs.

It is the short leash of allowed doubting, where questioning is equated to faithlessness, at which point one’s salvation is called into question. Next comes the looks of contempt from others, then gossip and even verbal condemnations. Thus for me and for most, the simple solution to prevent eternal damnation was to take the Bible at face value, forget my musings, and move on.

I think a lot of folks fit this mold: We believe in a higher power but still have gaps in our understanding. Subconsciously, however, we fear and are often reminded that to question our religious traditions is, somehow, sacrilegious. In my case at least, the years of country living, often wandering the hills and hollows alone, had produced a recklessly independent spirit. At times I was outspoken on the cognitive dissidence I saw in religious doctrine. I was a good kid, but learned early on to think for myself, to assume nothing and to “take the bull by the horns” as we used to say.

Though my inclination was always moral, I’d fight at the drop of a hat for what I believed to be the truth. Fear tactics, religious or otherwise, usually didn’t work with me. If something was broken, I figured it out and fixed it. If a question remained unanswered, I figured it out and answered it. Likewise my belief in God was no less matter of fact. I wanted to know, and no amount of religious-guilt could stifle my ponderings.

However, aside from an inherent rebellious streak, I was otherwise as normal as the next person. Life was simple then; I had a family, I had a job, and I had a god. At age 24 I worked every day and went to church almost every Sunday. I loved, protected and provided for my family. That of course is what made the next episode of my time on Earth all the more bizarre. Indeed, before the experience of which you are about to learn, I was a typical rural American of the late 1980s; and though my life was seemingly stable in every way, it would all come crashing down in the blink of an eye.

That Wednesday at the concrete plant began like any other. The noise and bustle of trucks, the growl of the huge mixer plant and the smell of cement and diesel all filled the senses. It was a hot day, July fifth as I recall, and we typically left the shop’s large overhead doors open on either end. This allowed a cooling breeze to pass through and more light as well.

Arou

nd 2:00 p.m. I stepped outside the door on the north end of the building so as to view the lot through which the trucks staged before loading. On the left side of my field of view was the mixer plant itself, an imposing structure, about six stories tall. To the right a bit and in my center-view, was a separate smaller building that contained both the dispatcher’s office on the second floor, along with the driver’s room directly below. Finally, to the right of that was the parking sheds and gate #3 through which the trucks exited.

The lot was typically muddied from a spray-bar that rinsed the trucks as they departed from under the mixer. This slurry covered the entire drive area, all except one slightly elevated section just in front of the dispatchers’ office. As the sun baked this flat, dusty patch, a whirlwind arose that colored itself with sand and powdered cement. It was quite the novelty, harmless of course, but seemingly with a life of its own. I watched as the wind revealed itself through the medium of filth, ascending almost as high as the mixer plant until finally losing momentum.

However, as the swirls dissipated I again lowered my attention to the place where they began, noticing a rather odd sight: an elderly man who I hadn’t noticed only moments before. He wore a navy-blue suit and sported an odd-looking red and blue cravat. “WOW”; I thought, as he resembled an English gentleman from the late Victorian era. This guy was completely out of place or at least in the wrong century, I humored, as was his mustache which, white as snow, also reflected that period.

He was a short fellow, mostly bald, but nifty-looking, well-dressed and equally lost too. What’s more, he was standing dangerously close to the lanes through which the trucks entered and exited the factory.

Probably another dreaded salesman, I thought to myself.

Unwanted solicitors were a daily nuisance at the plant. So to see a suit and tie roaming the lot wasn’t unusual. We had a standing order though: -no salesmen in the production area-. I’d run off my own share of salesmen over the years, yet this time I was hoping that someone else would beat me to the dirty deed. By the nature of their job, most salespeople can’t take no for an answer, and I dreaded the inevitable sales pitch, for which I had neither the time nor humor that day. That said, I had no intention of being disrespectful to someone of his age and frail stature.

I turned to my coworker, Larson, and inquired if he recognized the man, but by the time we looked out again, maybe 10 seconds later, the old fellow was gone.

Huh, perhaps he had walked just out of sight on the other side of the idling trucks, I surmised.

Larson, an older man himself and only two years from retirement, glared at me with disdain as though I’d lied. He was a veteran of World War II and likely due to his combat experience was predictably serious. He cared little for the camaraderie of the younger men with whom he worked. We were always up to something, and, here again, he was distrustful of my claim about the little old man. For once however I wasn’t crying wolf, yet I had no illusions as to why Larson didn’t believe me.

Whatever, I thought, and went back to work.

Thus we labored for about another hour, processing and stacking a new shipment of tires that had arrived earlier that morning. As a matter of routine, I again walked to the overhead door after completing the task. Much to my surprise, there stood the same little old man in the truck lot, sorely out of place as before.

Was he waiting for someone? I pondered.

Just as before, he was about 50 yards away standing just in front of the dispatchers’ building. From what I could tell at that distance, he appeared to have a 10,000-yard stare, randomly scanning some non-existent horizon and completely oblivious to his surroundings. Oddly, he seemed happy enough (he was smiling from ear-to-ear), but nonetheless his eyes looked hollowly through, instead of at, anything. I began to wonder if he was a salesman after all, that perhaps he was senile and had somehow wandered onto the property. I scanned the area for an out-of-place vehicle but saw nothing.

On the second story of the dispatch office was a large window from which Tommy and Eddie could view and coordinate the loading process of the trucks. Likewise they could see me as I stepped outside the garage and waved. They waved back, at which I pointed to the old man and scrunched my shoulders as if to say, “Who is that?” At this, they looked at each other and returned the gesture as if they didn’t understand what I was trying to say.

Again I called Larson from the back of the shop to see if he could recognize our hapless visitor. Just as before, however, when he walked to the overhead door, the elderly man was gone. By little surprise this merited a brutal but colorful cussing from my fellow worker who was now convinced I was an idiot.

“Let’s get to work,” he commanded, “and quit horse’n around.”

(This is a greatly abbreviated and rated-G version of what he actually said.)

Larson was, perhaps, the most fluent curser in the whole world—or at least that I’d ever known. Indeed, Edgar Allen Poe himself would have been hard-pressed to find the words of verbal discontent as well as Larson. And while it would be nice to assume that he meant no-ill by his slurs, my experience told me better. That said, his verbal displays were quite entertaining and made a believer to all those around him. He was feudalistic by nature, born and bred in the Appalachian traditions of eastern Kentucky. Yet it was his crack-whip attitude that forced me to walk the line of proof before comment.

In this case, however, the little old man had put me in bad rapport twice and I was more than a little frustrated. My thought at that point was that perhaps he’d walked inside the drivers’ room on the first floor of the dispatch office. It was air-conditioned with a restroom and a Coke machine, so it made sense that he retreated there to escape the blistering heat. Either way, it wasn’t my problem now. Surely one of the drivers would either help or evict the elderly gentleman.

At this I walked back inside the garage and took a drink from the water fountain. I suppose however that my curiosity got the better, so I again returned to the doorway to see what I could see. As you likely guessed, there stood the old man once again, this time facing slightly away and toward the north. “Okay, enough.” I thought, and immediately advanced, determined to prove to Larson that I’d been telling the truth about this illusive individual. “Great,” I said under my breath; the factory was loud and would mask my approach until I was upon him.

Now at this point it seemed simple enough to either assist or inquire as to the man’s motives for standing in the middle of the truck lot. But had I known what was about to happen or how it was to impact my life, it’s quite possible I would have instead run the opposite direction. As I’ve said before, till that moment I’d lived a mostly normal life: I played ball in school, was married, and worked a normal job. I’ve never used drugs and, at the time, didn’t drink alcohol. From what I can discern, there was nothing that could have induced such an event as that which occurred next.

As the distance closed between us, I further studied his small frame and trembling demeanor. He appeared to have Parkinson’s and shook greatly as he stood, seemingly unaware of my advance from his blind-side. At this, I reached out and gently touched his right shoulder, speaking only loud enough to gain his attention without frightening him:

“Can I help you with something, sir”, to which, at a distance of about two feet, he turned, looked me right in the eyes, face beaming with the brightest of light and said:

“You must be Daniel…”

Shocked by the fact that he knew my name and having never seen such awesome joy on a human face, I could only stutter,

“Do . . . do I know you?”

“No, but neither do you know yourself. But I know you,” he laughed.

At the same moment he reached out and lightly held the end of my still outstretched hand. As his hand touched mine, I was instantly engulfed with a feeling of bliss and peace beyond anything that I can describe with words. It was an instant state of stupor. I was frozen, completely taken in the moment as if by some magic, amazed, unable to r

etract my hand and equally unwilling to let go.

And then he began to speak:

“Do you know what your name means? Some people say that it means ‘God is my judge,’ but they are wrong. It means ‘Judge of God’ and I can assure you, my son, that there are wonderful things in store. I am here to help you remember.”

He continued talking, listing my life occurrences, things that no one, –no one!—knew: things from my childhood, my innermost thoughts, my fears, and even things that I’d never spoken.

“Do you remember when you were in the sixth grade and the bully was beating you up in the bathroom at school? You felt alone and scared, but I was there, then, and have always been with you.” (with a bubbling laugh of Joy)

“No matter the circumstances, everything you’ve suffered was to prepare you for this time. Ah, and what a special time it is. But you sensed it, didn’t you? You felt it; you knew it was coming. The truth is so wonderful. You are very lucky, very lucky indeed.” (more laughter)

“The day is here; no matter how trivial or how great, it all brought us to right now.” (continuing with jubilant laughter) “Let me share with you …”

He continued speaking without pause, his trembling not from Parkinson’s but from an irresistible joy, the likes of which I’d never witnessed. It exceeded anything I’d ever seen in a human being. What’s more, that same energy was entering through his touch and into me; and as it did, I lost track of his speech, the words becoming an inaudible garble.

Yet a part of me needed to know that someone else was seeing this event. Thus I managed with the greatest difficulty to glance upward toward the dispatchers. My head felt like it was tied to a huge elastic band pulling in the opposite direction, slowing my movement to a snail’s pace. I persisted, however, until finally, somehow, Tommy and Eddie were in the periphery of my view. There they stood leaning over their desks, peering downward with puzzled expressions, viewing this interaction between myself and this, (Okay), not-so-lost little old man.

The Book of Daniel and the Mystery of the Resurrection Machine

The Book of Daniel and the Mystery of the Resurrection Machine